After spending the weekend in Mammoth Caves National Park (highly recommended, by the way), the experience there has re-enforced some notions I have been harboring about the rangers that rove around our National Park system.

Thing is, they are very highly developed ambassadors between the wonders of the park and you, the public. They are not the bumbling, green-clad rangers of olden times, content to just sit back and lead silver-haired tourists around the hotel lobby, or sit in the ranger station and wait for the "SOS" plea to come over. These rangers today are highly educated, motivated people. And as the public, you should take full advantage of what they have to offer.

This summer I spent some time in the Tuolumne with friends, and we decided to go on a ranger-led hike to Mono Pass. The ranger who came with us was a female who was taking a break from her graduate work to be a ranger. She had a wealth of knowledge about the flora of the high alpine Sierra, as well as the complicated glaciation that helped carve out the valleys through which we hiked. She was environmentally-aware, giving us the back story of Mono Lake and the current efforts to preserve it. She turned what would have been an interesting, but fairly routine, hike into a walk of discovery among the granite peaks.

The same happened this weekend past. Going into the caves, the tour group was over 100 strong, too big for my tastes. As there was a ranger at the back to help keep prodding people along, we stayed back with him. With most of the people thronging ahead to be first in line, we essentially had our own personal guide through the park. He was an active caver himself, part of a team of volunteers who map new sections of the cave. He knew the history, the geology, and the intricacies of the cave system. He was engaging, friendly, and very helpful, making it a delightful tour.

I have been too austere with interacting with these guides and guardians in the past, but these experiences have taught me better. These interactions can add an untold dimension to your overall visit and experience of the park, making it richer and more rewarding than if you had gone it alone. Now there is always a time for personal exploration, but don't eschew the company of these green-hatted servants of the park; they just might clue you into something you've never known about.

I doff my hat to you, great rangers. Keep up the good work.

Sunday, October 21, 2007

Friday, September 29, 2006

Explorer of the Week, vol.9

Giovanni Caboto (c. 1450 – c.1499), known in English as John Cabot, was an Italian navigator and explorer commonly credited as the first early modern European to discover the North American mainland, in 1497, notwithstanding Leif Ericson's landing (circa 1000).

Cabot was born in either 1450 or 1451 in Genoa, Gaeta, or Chioggia. When he was 11, he moved to Venice and became a Venetian citizen. Like other Italian explorers of the era, such as Christopher Columbus (Cristoforo Colombo), Cabot made another country his base of operations. For Cabot it was England, so his explorations were made under the English flag. The voyage that saw him and his crew discover the North American mainland – the first Europeans known to do so since the Vikings – took place in 1497, five years after Columbus' discovery of the Caribbean. Again, like Columbus, Cabot's intention had been to find a westerly sea route to Asia.

It was probably on hearing of Columbus's discovery of 'the Indies' that he decided to find a route to the west for himself. He went with his plans to England, because he incorrectly thought spices were coming from northern Asia; and a degree of longitude is shorter the further one is from the equator, so the voyage from western Europe to eastern Asia would be shorter at higher latitudes.

King Henry VII of England gave him a grant to go on "full and free authoritie, leave, and power, to sayle to all partes, countreys, a see as, of the East, of the West, and of the North, under our banners and ensignes, with five ships ... and as many mariners or men as they will have in saide ships, upon their own proper costes and charges, to seeke out, discover, and finde, whatsoever iles, countreyes, regions or provinces of the heathen and infidelles, whatsoever they bee, and in what part of the world soever they be, whiche before this time have beene unknowen to all Christians."

Cabot went to Bristol to make the preparations for his voyage. Bristol was the second-largest seaport in England, and during the years from 1480 onwards several expeditions had been sent out to look for Hy-Brazil, an island said to lie somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean according to Celtic legends. Some people even think Newfoundland may have been found on one of these voyages.

In 1496 Cabot set out from Bristol with one ship. But he got no further than Iceland and was forced to return because of disputes with the crew. On a second voyage Cabot again used only one ship with 18 crew, the Matthew, a small ship (50 tons), but fast and able. He departed on either May 2 or May 20, 1497 and sailed to Dursey Head, Ireland. From there he sailed due west to Asia - or so he thought. He landed on the coast of Newfoundland on June 24, 1497. His precise landing-place is a matter of controversy, either Bonavista or St. John's. He went ashore to take possession of the land, and explored the coast for some time, and probably departed on July 20. On the homeward voyage his sailors thought they were going too far north, so Cabot sailed a more southerly course, reaching Brittany instead of England, and on August 6 arrived back in Bristol.

The location of Cabot's first landfall is not definitely known, due of lack of surviving evidence. Many experts think it was on Cape Bonavista, Newfoundland, but others look for it in Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Labrador, or Maine. Cape Bonavista, however, is the location recognised by the governments of Canada and the United Kingdom as being Cabot's official landing. His men may have been the first Europeans to set foot on the American mailand since the Vikings. Christopher Columbus did not find the mainland until his third voyage, in 1498, and letters referring to a voyage by Amerigo Vespucci in 1497 are generally believed to have been forgeries or fabrications.

Back in England, Cabot was made an admiral, rewarded with £10 and a patent was written for a new voyage. Later, a pension of £20 a year was granted him. The next year, 1498, he departed again, with 5 ships this time. The expedition made for an Irish port, because of distress. Except for one ship, Cabot and his expedition were never heard from again and are presumed to have been lost at sea. John's son, Sebastian Cabot, later made a voyage to North America, looking for the hoped for Northwest Passage (1508), and another to repeat Magellan's voyage around the world, but which instead ended up looking for silver along the Río de la Plata (1525-8).

Cabot was born in either 1450 or 1451 in Genoa, Gaeta, or Chioggia. When he was 11, he moved to Venice and became a Venetian citizen. Like other Italian explorers of the era, such as Christopher Columbus (Cristoforo Colombo), Cabot made another country his base of operations. For Cabot it was England, so his explorations were made under the English flag. The voyage that saw him and his crew discover the North American mainland – the first Europeans known to do so since the Vikings – took place in 1497, five years after Columbus' discovery of the Caribbean. Again, like Columbus, Cabot's intention had been to find a westerly sea route to Asia.

It was probably on hearing of Columbus's discovery of 'the Indies' that he decided to find a route to the west for himself. He went with his plans to England, because he incorrectly thought spices were coming from northern Asia; and a degree of longitude is shorter the further one is from the equator, so the voyage from western Europe to eastern Asia would be shorter at higher latitudes.

King Henry VII of England gave him a grant to go on "full and free authoritie, leave, and power, to sayle to all partes, countreys, a see as, of the East, of the West, and of the North, under our banners and ensignes, with five ships ... and as many mariners or men as they will have in saide ships, upon their own proper costes and charges, to seeke out, discover, and finde, whatsoever iles, countreyes, regions or provinces of the heathen and infidelles, whatsoever they bee, and in what part of the world soever they be, whiche before this time have beene unknowen to all Christians."

Cabot went to Bristol to make the preparations for his voyage. Bristol was the second-largest seaport in England, and during the years from 1480 onwards several expeditions had been sent out to look for Hy-Brazil, an island said to lie somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean according to Celtic legends. Some people even think Newfoundland may have been found on one of these voyages.

In 1496 Cabot set out from Bristol with one ship. But he got no further than Iceland and was forced to return because of disputes with the crew. On a second voyage Cabot again used only one ship with 18 crew, the Matthew, a small ship (50 tons), but fast and able. He departed on either May 2 or May 20, 1497 and sailed to Dursey Head, Ireland. From there he sailed due west to Asia - or so he thought. He landed on the coast of Newfoundland on June 24, 1497. His precise landing-place is a matter of controversy, either Bonavista or St. John's. He went ashore to take possession of the land, and explored the coast for some time, and probably departed on July 20. On the homeward voyage his sailors thought they were going too far north, so Cabot sailed a more southerly course, reaching Brittany instead of England, and on August 6 arrived back in Bristol.

The location of Cabot's first landfall is not definitely known, due of lack of surviving evidence. Many experts think it was on Cape Bonavista, Newfoundland, but others look for it in Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Labrador, or Maine. Cape Bonavista, however, is the location recognised by the governments of Canada and the United Kingdom as being Cabot's official landing. His men may have been the first Europeans to set foot on the American mailand since the Vikings. Christopher Columbus did not find the mainland until his third voyage, in 1498, and letters referring to a voyage by Amerigo Vespucci in 1497 are generally believed to have been forgeries or fabrications.

Back in England, Cabot was made an admiral, rewarded with £10 and a patent was written for a new voyage. Later, a pension of £20 a year was granted him. The next year, 1498, he departed again, with 5 ships this time. The expedition made for an Irish port, because of distress. Except for one ship, Cabot and his expedition were never heard from again and are presumed to have been lost at sea. John's son, Sebastian Cabot, later made a voyage to North America, looking for the hoped for Northwest Passage (1508), and another to repeat Magellan's voyage around the world, but which instead ended up looking for silver along the Río de la Plata (1525-8).

Monday, September 18, 2006

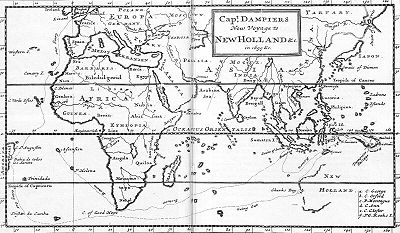

Explorer of the Week, vol.8

William Dampier was born at East Coker in Somerset and baptised on 8 June 1652. He went to sea at the age of 16. He served with Edward Sprague in the Third Anglo-Dutch War and fought at the Battle of Schooneveld in June 1673. In 1674 he worked as a plantation manager on Jamaica, but he soon returned to the sea.

In the 1670s he crewed with buccaneers on the Spanish Main of Central America, twice visiting the Bay of Campeachy. This led to his first circumnavigation: in 1679 he accompanied a raid across the Isthmus of Darién in Panama and captured Spanish ships on the Pacific coast of that isthmus; the pirates then raided Spanish settlements in Peru before returning to the Caribbean.

Dampier made his way to Virginia, where in 1683 he engaged with a privateer named Cook. Cook entered the Pacific via Cape Horn and spent a year raiding Spanish possessions in Peru, the Galapagos Islands, and Mexico. This expedition collected buccaneers and ships as it went along, at one time having a fleet of ten vessels. In Mexico Cook died, and a new leader, Captain Davis, took command. Dampier transferred to Captain Charles Swan's ship, the Cygnet, and on 31 March 1686 they set out across the Pacific to raid the East Indies, calling at Guam and Mindanao. Leaving Swan and 36 others behind, the rest of the pirates cruised to Manila, Pulo Condore, China, the Spice Islands, and New Holland (Australia).

Early in 1688 Cygnet was beached on the northwest coast of Australia, near King Sound. While the ship was being careened Dampier made notes on the fauna and flora he found there. Later that year, by agreement, he and two shipmates were marooned on one of the Nicobar Islands. They built a small craft and sailed it to Acheen in Sumatra. After further adventures Dampier returned to England in 1691 via the Cape of Good Hope, penniless but in possession of his journals.

The publication of these journals as New Voyage Round the World in 1697 created interest at the British Admiralty and in 1699 Dampier was given the command of HMS Roebuck with a commission to explore Australia and New Guinea.

The expedition set out on 14 January 1699, and on July 1699 he reached Dirk Hartog Island at the mouth of Shark Bay in Western Australia. In search of water he followed the coast northeast, reaching the Dampier Archipelago and then Roebuck Bay, but finding none he was forced to bear away north for Timor. Then he sailed east and on 1 January 1700 sighted New Guinea, which he passed to the north. Sailing east, he traced the southeastern coasts of New Hanover, New Ireland and New Britain, discovering the Dampier Strait between these islands (now the Bismarck Islands) and New Guinea.

On the return voyage to England, Roebuck foundered near Ascension Island on 21 February 1701 and the crew were marooned there for five weeks before being picked up on 3 April and returned home in August 1701. Although many papers were lost with the Roebuck, Dampier was able to save many new charts of coastlines, trade winds and currents in the seas around Australia and New Guinea.

He wrote an account of the 1699–1701 expedition, A Voyage to New Holland and returned to privateering. The War of the Spanish Succession broke out in 1701 and English privateers were being readied to assist against French and Spanish interests. Dampier was appointed commander of the 26-gun government ship St George, with a crew of 120 men. They were joined by the 16-gun galleon Cinque Ports (63 men) and sailed on April 30, 1703. En-route they unsuccessfully engaged a French ship but captured three small Spaniard ships and one vessel of 550 tons.

However, The expedition was most notable for the events surrounding Alexander Selkirk. The captain of the Cinque Ports, Thomas Stradling fell out with Sailing Master Selkirk. In October 1704 the Cinque Ports had stopped at the uninhabited Juan Fernández Islands off the coast of Chile to resupply. Selkirk had grave concerns about the seaworthiness of Cinque Ports and after a disagreement with Dampier, he opted to remain on the island. Selkirk was to remain marooned for four years and 4 months and his experiences were to become the inspiration for Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe. Selkirk's misgivings were fully justified: Cinque Ports did later sink with the loss of most of her crew. Dampier returned to England in 1707 and in 1709 his A Continuation of a Voyage to New Holland was published.

Dampier was engaged in 1708 by the privateer Woodes Rogers as sailing master on the Duke. This voyage was more successful: Selkirk was rescued on 2 February 1709, and the expedition amassed nearly £200,000 of profit. However, Dampier died in London in 1715 before he received his share.

He had an unusual degree of influence on figures better known than he:

* His observations and analysis of natural history helped Charles Darwin's and Alexander von Humboldt's development of their theories,

* He made innovations in navigational technology that were studied by James Cook and Horatio Nelson.

* Daniel Defoe, author of Robinson Crusoe, was inspired by accounts of real-life castaway Alexander Selkirk, a crew-member on Dampier's voyages.

* His reports on breadfruit led to William Bligh's ill-fated voyage in HMS Bounty.

* He is cited over a thousand times in the Oxford English Dictionary.

WD's second circumnavigation

Friday, September 01, 2006

Explorer of the Week, vol.7

Hugh Clapperton

Hugh Clapperton (May 18, 1788 - April 13, 1827), Scottish traveller and explorer of West and Central Africa.

Hugh Clapperton (May 18, 1788 - April 13, 1827), Scottish traveller and explorer of West and Central Africa.He was born in at Annan, Dumfriesshire, where his father was a surgeon. He gained some knowledge of practical mathematics and navigation, and at thirteen was apprenticed on board a vessel which traded between Liverpool and North America. After having made several voyages across the Atlantic Ocean, he was impressed for the navy, in which he soon rose to the rank of midshipman. During the Napoleonic Wars he saw a good deal of active service, and at the storming of Port Louis, Mauritius, in November 1810, he was first in the breach and hauled down the French flag.

In 1814 he went to Canada, was promoted to the rank of lieutenant, and to the command of a schooner on the Canadian lakes. In 1817, when the flotilla on the lakes was dismantled, he returned home on half-pay. In 1820 Clapperton removed to Edinburgh, where he made the acquaintance of Walter Oudney, who aroused in him an interest in African travel.

Lieutenant G. F. Lyon, having returned from an unsuccessful attempt to reach Bornu from Tripoli, the British government determined on a second expedition to that country. Walter Oudney was appointed by Lord Bathurst, then colonial secretary, to proceed to Bornu as consul and Hugh Clapperton and Dixon Denham were added to the party. From Tripoli, early in 1822, they set out southward to Murzuk, and from this point Clapperton and Oudney visited the Ghat oasis. Kuka, of Bornu, was reached in February 17, 1823, and Lake Chad seen for the first time by Europeans. At Bornu the travellers were well received by the sultan; and after remaining in the country until December 14 they again set out for the purpose of exploring the course of the Niger.

At Murmur, on the road to Kano, Oudney died (January 1824). Clapperton continued his journey alone through Kano to Sokoto, the capital of the Fula Empire, where by order of Sultan Bello he was obliged to stop, though the Niger was only five days' journey to the west. Worn out with his travel he returned by way of Zaria and Katsina to Kuka, where he again met Denham. The two travellers then set out, for Tripoli, reached on the January 26, 1825. An account of the travels was published in under the title of Narrative of Travels and Discoveries in Northern and Central Africa in the years 1822 - 1823 and 1824 (1826).

Immediately after his return Clapperton was raised to the rank of commander, and sent out with another expedition to Africa, the sultan Bello of Sokoto having professed his eagerness to open up trade with the west coast. Clapperton landed at Badagry in the Bight of Benin, and started overland for the Niger on the December 7 1825, having with him his servant Richard Lemon Lander, Captain Pearce, and Dr. Morrison, navy surgeon and naturalist. Before the month was out Pearce and Morrison were dead of fever. Clapperton continued his journey, and, passing through the Yoruba country, in January 1826 he crossed the Niger at Bussa, the spot where Mungo Park had died twenty years before. In July he arrived at Kano. Thence he went to Sokoto, intending afterwards to go to Bornu. The sultan, however, detained him, and being seized with dysentery he died near Sokoto.

Clapperton was the first European to make known from personal observation the semi-civilized Hausa countries, which he visited soon after the establishment of the Sokoto Empire by the Fula. In 1829 appeared the Journal of a Second Expedition into the Interior of Africa, &c., by the late Clapperton, to which was prefaced a biographical sketch of the explorer by his uncle, Lieut.-colonel S. Clapperton.

Richard Lemon Lander, who had brought back the journal of his master, also published Records of Captain Clapperton's Last Expedition to Africa . . . with the subsequent Adventures of the Author (2 volumes, London, 1830).

Monday, August 28, 2006

Explorer of the Week, vol.6

Jean-François Galaup was born near Albi, France. La Pérouse was the name of a family property which he added to his name. He studied in a Jesuit college, and entered the naval college in Brest when he was fifteen, and fought the British off North America in the Seven Years' War. In the beginning of the war he was wounded in a naval engagement off the French coast and was briefly imprisoned. He was promoted to rank of commodore when he defeated the English frigate Ariel in the West Indies. In August 1782 he made fame by capturing two English forts on the coast of the Hudson Bay, but left the survivors with food and ammunition when he departed.

Scientific expedition

La Pérouse was appointed in 1785 to lead an expedition to the Pacific. His ships were the Astrolabe and the Boussole, both 500 tons. They were storeships, reclassified as frigates for the occasion. One of the men who applied for the voyage was a 16-year-old Corsican named Napoleon Bonaparte. He was a second lieutenant from Paris's military academy at the time. He made the preliminary list but he wasn't chosen for the final list and remained behind in France. The rest, regarding him, is history. La Pérouse was a great admirer of James Cook, tried to get on well with the Pacific islanders, and was well-liked by his men.

Alaska, Japan, and Russia

He left Brest on August 1, 1785, rounded Cape Horn, investigated the Spanish colonial government in Chile, and, by way of Easter Island(where he stayed for only two days) and Hawaii[, sailed on to Alaska, where he landed near Mount St. Elias in late June 1786 and explored the environs. Next he visited Monterey, arriving on September 14, 1786. He examined the Spanish settlements and made critical notes on the treatment of the Indians in the Franciscan missions.

The next year he set out for the northeast Asian coasts. He saw the island of Quelpart (Cheju), which had been visited by Europeans only once before when a group of Dutchmen shipwrecked there in 1635. He visited the mainland coast of Korea, then crossed over to Oku-Yeso (Sakhalin).

The inhabitants had drawn him a map, showing their country, Yeso (also Yezo, now called Hokkaido) and the coasts of Tartary (mainland Asia). La Pérouse wanted to sail through the channel between Sakhalin and Asia, but failed, so he turned south, and sailed through La Pérouse Strait (between Sakhalin and Hokkaido), where he met the Ainu, explored the Kuriles, and reached Petropavlovsk (on Kamchatka peninsula) on September 7, 1787. Here they rested from their trip, and enjoyed the hospitality of the Russians and Kamchatkans. In letters received from Paris he was ordered to investigate the settlement the British were to erect in New South Wales.

Pacific

His next stops were in the Navigator Islands (Samoa), on December 6, 1787. Just before he left, the Samoans attacked a group of his men, killing twelve of them, among which were Lamanon and de Langle, commander of the Astrolabe. Twenty men were wounded. The expedition continued to Tonga and then to Australia, arriving at Botany Bay on 26 January 1788. The British received him courteously, but were unable to help him with food as they had none to spare. La Pérouse sent his journals and letters to Europe with a British ship, the Sirius, obtained wood and fresh water, and left for New Caledonia, Santa Cruz, the Solomons, the Louisiades, and the western and southern coasts of Australia. Although he wrote that he expected to be back in France by June 1789, neither he nor any of his men was seen again.

Discovery of the expedition

On September 25, 1791, Rear Admiral Joseph Antoine Bruni d'Entrecasteaux departed Brest in search of La Pérouse. His expedition followed La Pérouse's proposed path through the islands northwest of Australia while at the same time making scientific and geographic discoveries. In May of 1793, he arrived at the island of Vanikoro, which is part of the Santa Cruz group of islands. d'Entrecasteaux thought he saw smoke signals from several elevated areas on the island, but was unable to investigate due to the dangerous reefs surrounding the island and had to leave. He died two months later.

It was not until 1826 that an Irish captain, Peter Dillon, found enough evidence to piece together the events of the tragedy. In Tikopia (one of the islands of Santa Cruz), he bought some swords he had reason to believe had belonged to La Pérouse. He made enquiries, and found that they came from nearby Vanikoro, where two big ships had broken up. Dillon managed to obtain a ship in Bengal, and sailed for Vanikoro where he found cannon balls, anchors and other evidence of the remains of ships in water between coral reefs. He brought several of these artifacts back to Europe, as did D'Urville in 1828. De Lesseps, the only member of the expedition still alive at the time, identified them, as all belonging to the Astrolabe. Both ships had been wrecked on the reefs, the Boussole first. The Astrolabe was unloaded and taken apart. A group of men, probably the survivors of the Boussole, were massacred by the local inhabitants. According to natives, surviving sailors built a two-masted craft from the wreckage of the Astrolabe, and left westward about 9 months later, but what happened to them is unknown. Also, two men, one a "chief" and the other his servant, had remained behind, surviving until 1823, three years before Dillon arrived.

Friday, August 18, 2006

Explorer of the Week, vol.5

Juan Ponce de León

(c. 1460 – July 1521) A Spanish conquistador. He was born in Santervás de Campos (Valladolid). As a young man he joined the war to conquer Granada, the last Moorish state on the Iberian peninsula. Ponce de León accompanied Christopher Columbus on his second voyage to the New World. He became the first Governor of Puerto Rico by appointment of the Spanish Crown. He is regarded as the first European known to have visited what is now the continental United States, as he set foot in Florida in 1513.

It is thought that Ponce first landed on the site where Cockburn Town is located, on Grand Turk in the Turks & Caicos Islands. Ponce de León settled in Hispaniola after arriving in the New World. He helped conquer the Tainos of the eastern part of Hispaniola, and was rewarded with the governorship of the Province of Higuey that was created there. While there he heard stories of the wealth of Boriken (now Puerto Rico), and he sought and received permission to go there. In 1508, Ponce de León founded the first settlement in Puerto Rico, Caparra (later relocated to San Juan).

The Fountain of Youth

The popular story that Ponce de León was searching for the Fountain of Youth when he discovered Florida is misconceived. He was seeking a spiritual rebirth with new glory, honor, and personal enrichment, not a biological rebirth through the waters of the Fountain of Youth. The Tainos had told the Spanish of a large, rich island to the north named Bimini, and Ponce de Leon was searching for gold, slaves and lands to claim and govern for Spain, all of which he hoped to find at Bimini and other islands. The story of Ponce de León searching for the Fountain of Youth seems to have surfaced in the 1560s in the Memoir of Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda, and was later included in the Historia general de los hechos de los Castellanos of Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas. The statue was made in New York in 1882 using the bronze from English cannons seized after the English attacked San Juan in 1792.

First voyage and discovery of Florida

Ponce de León equipped three ships at his own expense, and set out on his voyage of discovery and conquest in 1513. On March 27, 1513, he sighted an island, but sailed on without landing. On April 2 he landed on the east coast of the newly "discovered" land at a point which is disputed, but was somewhere on the northeast coast of the present State of Florida. Ponce de León claimed "La Florida" for Spain. He named the land La Florida, meaning flowery, either because of the vegetation in bloom he saw there, or because he landed there during Pascua Florida, Spanish for Flowery Passover, meaning the Easter season. Pascua Florida Day, April 2, is a legal holiday in Florida.

Ponce de León then sailed south along the Florida coast, charting the rivers he found, passed around the Florida Keys, and up the west coast of Florida to Cape Romano. He sailed back south to Havana, and then up to Florida again, stopping at the Bay of Chequesta (Biscayne Bay) before returning to Puerto Rico.

Ponce de León may not have been the first European to reach Florida. He encountered at least one Native American in Florida in 1513 who could speak Spanish.

Last Voyage

In 1521 Ponce de León organized a colonizing expedition on two ships. It consisted of some 200 men, including priests, farmers and artisans, 50 horses and other domestic animals, and farming implements. The expedition landed on the southwest coast of Florida, somewhere in the vicinity of the Caloosahatchee River or Charlotte Harbor. The colonists were soon attacked by Calusas and Ponce de León was injured by a poisoned arrow. After this attack, he and colonists sailed to Havana, Cuba, where he died. His tomb is in the cathedral in Old San Juan.

Thursday, August 17, 2006

La Via Alpina!

Via Alpina

The Alps are a unique area of almost 200,000km2 stretching over eight countries in Europe - France, Italy, Monaco, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Germany, Austria, and Slovenia. They are one of the top tourist destinations in the world.

It is an area that offers opportunities for exploring history and culture and allows visitors to experience the shared Alpine way of life, which can be discovered through an extensive network of local, regional, and national trails intended for walkers of all levels.

On the initiative of the French Association La Grande Traverseé des Alpes, institutions, associations, and professional organizations in these eight countries have been working to create the Via Alpina, the first recognized walking trail described in multilingual documentation linking Trieste on the Adriatic Coast to Monaco and the Mediterranean.

Via Alpina has been recognized as genuinely contributing to the implementation of the Alpine Convention, which seeks to ensure sustainable development in the Alps.

Facts/Figures

• The Via Alpina covers eight countries, 30 regions, canons or länder, and more than 200 communes.

• The Via Alpina passes from one shoreline to another and the highest point is at 3017m at the Niederjoch pass (Italian-Austrian border).

• The Via Alpina route that was revised and adopted by all those involved in early 2001 consists of five different sections: the red, purple, yellow, green, and blue trails, which together represent more than three hundred stages and approximately 5000km of walking trails.

• By Country (58 cross border stages)

o Italy: 121 stages

o Switzerland: 54 stages

o Germany: 30 stages

o Liechtenstein: 3 stages

o Austria: 70 stages

o France: 40 stages

o Slovenia: 22 stages

o Monaco: 1 stage

• Red Trail: 161 stages. Trail linking Trieste and Monaco across all eight countries.

• Purple Trail: 66 stages. Slovenia, Austria, Germany

• Yellow Trail: 40 stages. Italy, Austria, Germany

• Green Trail: 13 stages. Liechtenstein, Switzerland

• Blue Trail: 61 stages. Switzerland, Italy, France

The Alps are a unique area of almost 200,000km2 stretching over eight countries in Europe - France, Italy, Monaco, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Germany, Austria, and Slovenia. They are one of the top tourist destinations in the world.

It is an area that offers opportunities for exploring history and culture and allows visitors to experience the shared Alpine way of life, which can be discovered through an extensive network of local, regional, and national trails intended for walkers of all levels.

On the initiative of the French Association La Grande Traverseé des Alpes, institutions, associations, and professional organizations in these eight countries have been working to create the Via Alpina, the first recognized walking trail described in multilingual documentation linking Trieste on the Adriatic Coast to Monaco and the Mediterranean.

Via Alpina has been recognized as genuinely contributing to the implementation of the Alpine Convention, which seeks to ensure sustainable development in the Alps.

Facts/Figures

• The Via Alpina covers eight countries, 30 regions, canons or länder, and more than 200 communes.

• The Via Alpina passes from one shoreline to another and the highest point is at 3017m at the Niederjoch pass (Italian-Austrian border).

• The Via Alpina route that was revised and adopted by all those involved in early 2001 consists of five different sections: the red, purple, yellow, green, and blue trails, which together represent more than three hundred stages and approximately 5000km of walking trails.

• By Country (58 cross border stages)

o Italy: 121 stages

o Switzerland: 54 stages

o Germany: 30 stages

o Liechtenstein: 3 stages

o Austria: 70 stages

o France: 40 stages

o Slovenia: 22 stages

o Monaco: 1 stage

• Red Trail: 161 stages. Trail linking Trieste and Monaco across all eight countries.

• Purple Trail: 66 stages. Slovenia, Austria, Germany

• Yellow Trail: 40 stages. Italy, Austria, Germany

• Green Trail: 13 stages. Liechtenstein, Switzerland

• Blue Trail: 61 stages. Switzerland, Italy, France

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)